Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

Aquatic life requires a minimum level of dissolved oxygen present in the water for survival. When dissolved oxygen is below this critical level for organisms, fish and wildlife are harmed as a result. Some aquatic organisms, such as catfish, can survive when the concentration of dissolved oxygen is below 5.0 mg/L; however most, such as salmon, will suffer or perish.

Dissolved oxygen in the water column is influenced by re-aeration (photosynthesis, or adding oxygen to the water by phytoplankton; or physical processes such as waterfalls, or wind), and deoxygenation (respiration by microbiological organisms, or elevated water temperature).

Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), or the demand of oxygen by bacteria, is a widely used parameter for biodegradable organic matter in the aquatic environment. The common BOD test lasts five days. This five-day standard dates back to the inception of the test in the late 19th century, and the belief that it took five days for the River Thames to flow from London to the sea. At that time, sewage was released directly into the River Thames, which unfortunately worked its way back upstream during high tides.

Aerobic (oxygen consuming) bacteria metabolize rich organic matter (sewage, decaying plants and organisms), and deplete the water column of the dissolved oxygen. The organic matter is a readily available food source for cell maintenance and synthesis of new cell tissue.

COHNS + O2 + bacteria → CO2 + H2O + NH3 + other end products + energy

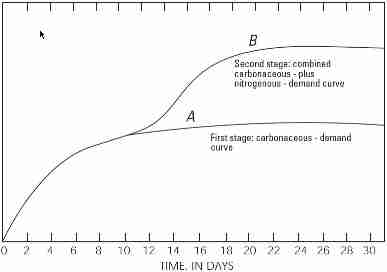

Because nitrogen (N) is also a product of respiration, it too can influence the BOD result. Two genera of bacteria, Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter, will oxidize the ammonia (NH3) to nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-), respectively. Typically, this takes more time than the 5-day BOD test (generally 6-10 days), but it can artificially increase the BOD result (Figure 1). For this reason, an inhibitor can be added by the laboratory upon request that suppresses the nitrification process, providing a carbonaceous BOD (CBOD) result.

Figure 1. Increase of oxygen demand by bacteria over time

(from http://inspectapedia.com/septic/BOD5_Wastewater_Test.php).

Controls are set with each day the BOD test is performed. First, the dilution water is checked. It is important to verify that the dilution water added to each sample bottle does not receive an unknown microbial population. The change in DO over the five-day incubation period should be <0.2 mg/L. This is also referred to as the negative control. Second, seed blanks are set. Generally, two to three bottles are set which contain a known amount of seed and dilution water. These bottles are used to quantify the amount of depletion that will occur from the known amount of seed added to each sample bottle. The amount of DO that should be attributed to seed uptake should be between 0.6 and 1.0 mg/L. Third, three bottles are set containing the dilution water, known volume of seed, and a controlled carbon source for the bacteria to consume: glucose-glutamic acid (GGA). The amount of GGA added should produce a known oxygen demand during the five-day incubation period, typically 198 ± 30.5 mg/L. This is also referred to as the positive control. In order for a BOD result to ‘count’, the change in DO over the 5-day incubation period must be >2 mg/L, and the DO value measured on day 5 must be >1 mg/L. If more than one dilution set meets these two requirements, the calculated BOD results are averaged and reported.

Similarly, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), is the demand of oxygen required to reduce dichromate (Cr2O72-, Cr in 6+ oxidation state) to Cr3+. The COD test is more robust than BOD because not all organic matter is readily oxidized by bacteria. Additionally, other chemicals, and inorganic substances in the water can be oxidized by dichromate. This allows for the COD test to be a proxy for BOD (COD>BOD), as long as a ratio between the two tests has been established. The COD analysis produces a more rapid response than the BOD analysis. While the BOD test takes five days to complete, the COD test can be completed in a few hours.

Samples submitted for regulatory compliance must be preserved to pH<2 with sulfuric acid and may be held up to 28 days from collection. Otherwise, Caltest will screen the BOD sample for informational purposes only. A low volume aliquot, 2 mL, is added to a vial containing the dichromate solution and a catalyst, usually mercury. The sample with all quality control checks (negative – laboratory water, positive – a solution known to give a particular response containing potassium hydrogen phthalate) are ‘digested’ on a hot block at 150°C for two hours. The vial is cooled before determining the concentration of the COD by color comparison on a spectrophotometer at a prescribed wavelength. The more the color of the vial changes from orange to green, the greater the COD of the sample.

Total Organic Carbon (TOC) can also be used in place of the COD test; however, it requires the entity responsible for the sample to determine the relationship (ratio) between TOC and BOD. TOC is performed on a sample preserved to pH<2 with acid (usually sulfuric but some instruments can analyze samples preserved with hydrochloric or phosphoric acid)and may be held up to 28 days from collection. It is only a matter of minutes from the time the sample is injected on the instrument to the generated response which makes the analysis faster than COD (but it still takes time to calibrate and verify the instrument runs properly throughout the analytical run to report the data). The TOC analysis converts all available organic carbon in the sample to carbon dioxide (CO2), which is measured by an infrared analyzer. The concentration in the sample is calculated using the response measured by the infrared analyzer and comparing it to the responses generated by a laboratory prepared calibration curve.

American Public Health Association (APHA). 2005. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Pollution Control Federation. 21st Edition, Washington, D.C.

Mayer, J. Richard. Environmental Case Studies. Benjamin/Cummings, 1997.

Mayer, J. Richard. Water Quality: Basic Principles and Experimental Methods. Western Washington University. 1999.

Metcalf & Eddy., George Tchobangoglous, Franklin L. Burton, and H. David Stensel. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Reuse. 4th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

For more information, or a quote, please call us or email info@caltestlabs.com